The Phoenix in History, Legend and Magick

vel Umbra Alarum

[This exploratory essay was originally published in 2008. I’m entering it here with edits for corrections, length, clarity, and some cringe. It began as an essay on the OTO’s Grade of Minerval, written by Crowley as a preliminary degree to MMM/OTO affiliation, but became much larger in scope. I hope the reader finds it more exhaustive than exhausting. The subject gives a great look into the sophistication of Crowley’s mysticism and penetrating insight into alchemy. More studied persons than I are invited to leave their thoughts and corrections in the comments.]

I would like to thank Dr. Hereward Tilton of the University of Amsterdam for his excellent research on the subject of Michael Maier's relation to the Phoenix itself. His patient advice directed me to several avenues which gave a new and different life to this essay. Thanks also to Br. S. L. G. of Alombrados in New Orleans for his help with the Latin and also Dr. Nutzkiewicz of the University of New Mexico for help with Midrashim and Hebrew. - Crow, 2008

Introduction

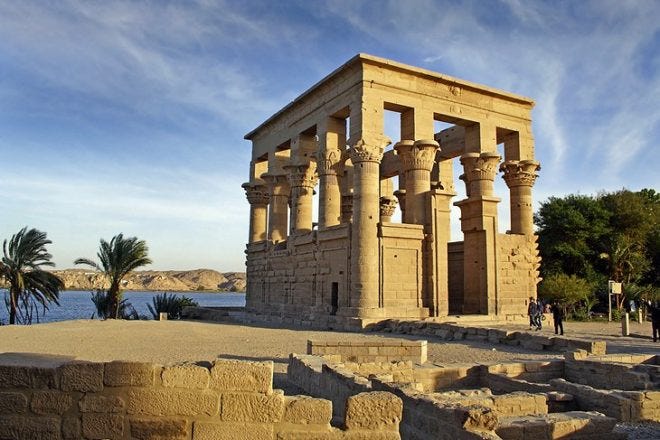

Yea, O my master, thou art the beloved of the Beloved One; the Bennu Bird is set up in Philae not in vain.

Liber 65, IV:22

Of the many mysteries of antiquity that survived into the modern age, precious few have gained a great deal of popularity. These few are often composite with modern religion and interpreted in light of that paradigm. One such memory is the bird called the phoenix, which is as commonly known now as when it was said to have lived. However, very little of this remarkable bird’s background is popularly preserved.

The modern image is that of some flaming bird that returns to life and is sometimes capable of resurrecting deceased heroes in popular role-playing games. The dominant motif is the power of re-birth, itself being capable of rising from its own ashes thereby surviving the most annihilating of ends, immolation, reduction to nothing but dust and ash. This power makes the phoenix as a symbol of triumph, overcoming the inevitable, and victory over the impossible. What is forgotten is the divine beauty of this bird and the complex method by which it accomplishes the miracle of resurrection.

The first half of this essay will take its data primarily from sources dating from classical Greece, Ancient Egypt and Arabia, and poetic adaptations of the Phoenix in, broadly considered, late-Renaissance literature in the Rosicrucian genres of Hermeticism and Alchemy. The second half will attempt to weave all of this into Crowley’s usage and references to make the lessons tangible and practical to the initiate magician.

The Myth of the Fire Bird

For the sake of crowning the symbol itself with a divine name I will refer to the subject of this essay as “the Phoenix,” preserving its Grecian title and the better known. Several appearances of the Phoenix will be treated more fully later, but for the present a migratory history can be built through the etymology of its various names.

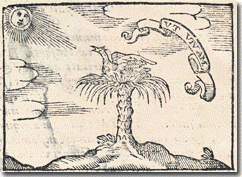

Phoenix is a Greek word with a few translations. Its root could be traced to the literal Greek phoinos, which means blood red or reddish-purple. The late Egyptian color scheme of the Phoenix follows suit. Curiously, Phoenix was also the Greek word for the Egyptian date palm. The connection between the Phoenix and the palm tree is treated more fully below. “Phoinos” is likely Semetic or even Mycenean in origin.

The bird and the palm tree’s sharing of a common name is not peculiar to the Greek. It is also the case in Egyptian, Hebrew, and Persian tongues. The double-meaning of Phoenix for the bird and the date palm may have arisen from the Ancient Egyptian. The Egyptian Bennu bird is the mythological origin of the Grecian phoenix. The word Bennu comes from weben, “to rise brilliantly,” or, “to shine.” Bennu was used to refer to both the Phoenix and the date palm. The date palm was given this resurrection role due to its hermaphroditic reproduction (self-fertilization), potentially leading the ancient man to believe it possessed the power of spontaneous generation, as did the Bennu Bird. Bennu is related to the Egyptian bnbn, “to copulate,” and referred to the mythical stone or mound of Heliopolis upon which the world was created. This connection is treated more fully below.

The Persian Huma shares many traits with the Egyptian Bennu and Greek Phoenix. Huma derives from the Persian word of power hum, the equivalent of the Sanskrit Om, and shares meaning with the Sufi word of power hu, and also the Arabic name for God, hua (Khan, 2005). The Sufi word of power Haqq, “truth,” is a composite of Hu, “God,” and Ek, “one.” Al-Haqq is also one of the 99 names of Allah in the Quran. The Prophet Zoroaster is said to be born of a Huma Tree, another connection between the palm and fire bird (Tame, 1984), though it is not a palm. The Huma bird’s role was one of granting luck, and should the Huma bird alight on a man’s head then that man was destined to become King. (Tame, 1984) Interestingly, in Egyptian hieroglyphs and statues, Pharaohs and Harpocrates were often depicted as having a Hawk protecting their head as if it were a part of the nemyss.

The Huma is mentioned by some sources to be involved in the rituals of the Tower of Silence, an antique Middle Eastern method of disposing of corpses. The connection could be through the ever-burning flame of the Zoroastrians kept within the Tower, the role of Birds in devouring the corpses contained therein, or the role of the Sun’s flames in the purification of the corpses. (Godrej and Mistree, 2002).

Some other fire birds are noteworthy. However, their relation to the western Phoenix is questionable.

The жар-пти́ца, Zhar Ptitsa, or “fire bird,” appears often in Russian folk-lore as a kind of trickster who initiates a quest for some young hero by dropping a feather. (Spirin, 2002) Once the hero collects the feather he begins a hunt for the Zhar Ptitsa, the trapping of which would grant some boon. Other than it being depicted as a peacock, very reminiscent of Late Greek and early Phoenician fire-birds, and having a flaming plumage, it does not bear the same power of resurrection as its cousins. However, the power of a phoenix feather is a recurrent motif in hermetic alchemy, appearing both in the works of Christian Rosencreutz and Michael Maier.

In the Far Eastern Orient similar fire-birds are of note; however, they share traits with the Phoenix only superficially. China’s 凤凰 Fenghuang dates to pre-historic times, but was more of a chimera.

Both etymologically and descriptively it is safe to assume that the western Phoenix derives largely from a Hellenic combination of the Egyptian Bennu and, to a lesser degree, the Arabian Huma.

The Phoenix of Ancient and Classical Greece

The Phoenix of Europe derives largely from the Hellenic Phoenix. This Phoenix’s myth seems to be in no way novel and merely a Grecian interpretation of the Heliopolitan myth. The Phoenix’s appearance in Greek literature is important to consider since this would have been the primary reference point for the revival of interest in the Phoenix in Europe. Greek authors were the first to deep dive into the allegorical nature of the Phoenix as an Aeonic device and metaphor for the soul.

The earliest reference to the Phoenix is the Precepts of Chiron where Hesiod ( who lived circa 700bc but the work is perhaps pseudepigraphic) simply discussed its longevity, saying, “A chattering crow lives out nine generations of aged men, but a stag's life is four time a crow's, and a raven's life makes three stags old, while the phoenix outlives nine ravens, but we, the rich-haired Nymphs, daughters of Zeus the aegis-holder, outlive ten phoenixes.” (Parada, 1997)

Of ancient Greek authors, the more informative description appeared three Centuries later in Herodotus’ Histories, and deserves to be quoted at length:

There is also another sacred bird called the phoenix, which I did not myself see except in painting, for in truth he comes to the Egyptians very rarely, at intervals, as the people of Heliopolis say, of five hundred years. They say that he comes regularly when his father dies; and if he be like the painting, he is of this size and nature, that is to say, some of his feathers are of gold color and others red, and in outline and size he is as nearly as possible like an eagle. This bird, they say (but I cannot believe the story), contrives as follows.

Setting forth from Arabia he conveys his father, they say, to the temple of the Sun plastered up in myrrh, and buries him in the temple of the Sun. He conveys him thus. He forms first an egg of myrrh as large as he is able to carry, and then he makes trial of carrying it, and when he has made trial sufficiently, then he hollows out the egg and places his father within it and plasters over with other myrrh that part of the egg where he hollowed it out to put his father in, and when his father is laid in it, it proves (they say) to be of the same weight as it was; and after he has plastered it up, he conveys the whole to Egypt to the temple of the Sun. Thus they say that this bird does.(124, Herodotus, 2003)

Herodotus’ account suggests that the Grecian phoenix was derived solely from Egypt. Tacitus' description in his Annals contains no other information than what Herodotus offers and it carries the same sound of reservation towards second hand information.

The information Greek authors most frequently referenced came from the priests of an Egyptian city called Heliopolis. This was a popular spot for philosopher pilgrims, including Plato, Solon, Hipparchus, and Pythagoras. This was due to its proximity to the Great Pyramids and other monoliths and also the Temple of Heliopolis. This temple is particularly important, for it was there that the Phoenix would undergo the necessary preparation for resurrection upon the “altar of the Sun.”

The resurrection of the Phoenix was also believed by Greeks to correlate with the transition of Aeons. This connection was explained by Manly P. Hall (2003, p. 231) and Aleister Crowley who, positing a 600ish year lifespan, saw three Phoenix-lives marking the three decans of whatever zodiac sign governed an Aeon. Crowley saw the Moses/Dionysus to Christ to Mohammad to Jacques de Molay or Martin Luther to himself as being marked by the Phoenix’s lifespan.

The Bennu Bird

O Atum-Khoprer, you became high on the height, you rose up as a bnbn-stone in the Mansion of the Bennu in On.

Pyramid Texts, utt 600, § 1652

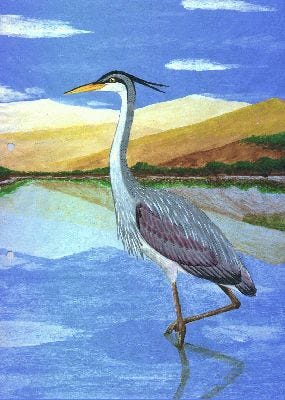

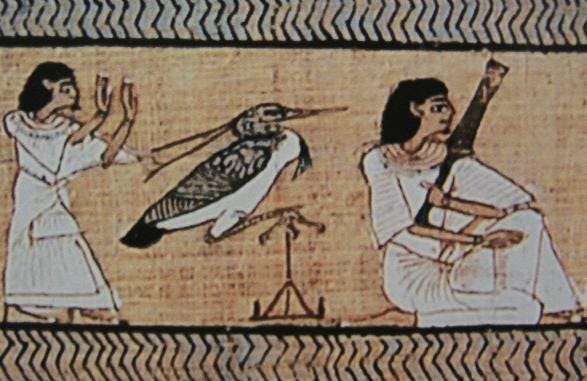

The Bennu’s hieroglyphic depiction shows a pre-historic Heron which populated the Egyptian Nile and Arabian Peninsula, Ardea bennuides. Its exact date of extinction is unknown; however, it did interact with men in a religious capacity before it went the way of the rest of the pre-historic megafauna. This is known by the recent (2006) discovery of Ardea Bennuides skeletons in the tombs of Umm al-Nar in modern UAE (UAE Interact, 2006). These tombs dated between 2700bc and 2000bc, which roughly corresponds to the period of time of the Old Egyptian Kingdom. While not their area of expertise, the German archaeologists who discovered these skeleton remains are confident in its connection to the Bennu bird. (Bestiarium, 2007) Further, this position in Arabia in proximity to Egypt and Philae corresponds to ancient authors description of the Bennu's migration from Arabia to Egypt. Arabia was the Bennu's home but Egypt was its holy land. None but the Ancient Egyptians argued for the Bennu's literal existence. The Greeks and onward all argued an allegorical interpretation and that the notion of its literal existence was preposterous.

Its plumage, depicted in hieroglyphs, varied between blue, purple, gold, and red with white. As a testament to its size there is an ancient temple for the rites of Isis and Osiris on the small island of Philae in Upper Egypt, and in this complex is a massive cage-like structure said to have housed the Bennu bird. (341, Massey, 1998) This cage is a monumental structure, and the Bennu would’ve been twice the size of an ostrich to be contained within Philae’s pillars, which matches the exhumed mummies in the UAE.

The Bennu bird is given a different life span by each source. These dates seem like typical antiquated exaggerations of life span, but as scholars of esotericism note, there is often mystical import behind the age of a period or person. Herodotus believed the lifespan to be around 500 years and Tacitus posited between 500, 1400, and 6100 years. The complex lifespan based on animal generations given in the Precepts of Chiron suggests around 1000 years. (Parada, 1997) Later authors were fond of Herodotus’ estimate and often agreed with around 600 years.

All authors agree that the pilgrimage site for the Bennu’s sacrifice is Heliopolis, the “city of the sun.” Heliopolis is a fascinating city in Egyptian history. It was called, “city of the pillars,” and the Hebrew title was On, spelled אֵן or אֵון, which recalls the Greek word for being (ὤν/On, as in Ontology), Hebrew word for Nothing (אֵין/Ain, as in Ain Soph) and Arabic word for the sun (عين/Oin). Many Greeks traveled to Heliopolis for education and initiation. Among other things, Heliopolis taught the mysteries of geometry and mathematics, which to both Pythagoras and Plato was the study of a noumenal and immutable world. These myths of Heliopolis explain the Bennu’s reason for trusting its life with these priests above all others.

The Bennu’s connection to Heliopolis’ study and application of this science of being may come from its use of music. The Bennu has the gift of song which the Pythagoreans, who derive their lineage from Heliopolis, greatly emphasized. Music was a way of “tuning” the mind to the world of numbers, harmony, and beauty. Likewise this was an educational exercise encouraged in Plato’s Republic. This is a possible reason Apollo or Helios visited the Phoenix (either at dawn or noon) to listen to its brilliant song while drinking from the well at which the Phoenix enjoyed its siesta of noon. The music trait was lost in later European adaptations.

Heliopolis’ central deity was Atum, the “self-created,” who willed himself into existence and then created the entire Heliopolitan ennead with a fascinating spell. Accounts vary and co-mingle with those of Ptah, the Memphis corollary of Atum, and Amoun, his Theban counterpart. He either spat, ejaculated via masturbation, or spake the other Gods into existence. The Egyptians, noting the curative effects of saliva, saw spitting as a means of blessing or bestowing health. This is the most common method of creation credited to Atum. However, he and Ptah were also believed to produce the Gods from semen, and the hand eventually came to replace the traditional hieroglyph for Atum. This symbolic connection of seed and hand is preserved in the Hebrew letter י/Yod which means hand but resembles a seed or small flame. Lastly, speaking Gods into existence is the method of Ptah, but the Egyptians used one word for speech and ejaculate, ḥkꜣ/Heka, which also means magick.

A strange motif in Egyptian mythology is self-fertilization. Atum, the primordial God of Heliopolis, impregnated himself with the next two Heliopolitan Gods. The lone date palm, a common sight of the Sahara, is a hermaphroditic plant, meaning that it is capable of self-fertilization. Since only one Bennu exists at a time it reproduced similarly. [see also my essay on Chaos]

The Benben (trans: to copulate) stone upon which Atum stood at the moment of creation has been interpreted as both “a stone” and “a mound.” The stone is described as that stone which surmounts the central pillar in Heliopolis or as the mound upon which everything was made and Heliopolis rests. Heliopolis was the home of Imhotep, the reputed inventor of stone-carving and creator of the step pyramid, pillar, and obelisk. This central pillar in Heliopolis is claimed to be an Obelisk of Imhotep’s design, being a pillar surmounted by a pyramidal black stone, identical to that stone which was held in reverence by the followers of Cybele in Rome, a frenzy cult imported from Anatolia. The Bennu bird’s altar for its incineration is believed to be an altar in the center of Heliopolis upon the Benben stone. This brings two important allusions. Atum standing on the Benben to create the ennead seems synchronous with the Bennu’s resurrection upon that very same stone. The alternative interpretation of Atum standing upon the “mound” bears no particular relevance to the Bennu outside of another text which places the Bennu on that mound, mentioned below. However, the idea that Atum spat/ejaculated/ uttered some creative formula to birth the Gods is also connected to the Huma bird of Persia whose name derives from Hu, the creative word of the Zoroastrians. Another more physical connection between the Bennu, Benben, and the palm is seen in the shape of the palm itself. The palm is a straight-standing pillar, similar to an obelisk, atop of which is a flourish of ray-like fronds very similar in appearance to an radiant sun. Were the Bennu to immolate itself atop a pillar it might appear very similar to a date palm.

Atum pre-dated existence, but stories differ as to how he arrived at the Benben. The Egyptologist Lasko relates, “Atum Kheper, you have come to be high on the hill, you have arisen on the Benben stone in the mansion of the Benben in Heliopolis,” (92, Baines, Silverman, and Lasko, 1991) where Atum-Kheper is Atum-Khephra, a composite of Atum and Khephra, the latter being the dung-beetle headed god that presides over the sun’s passage through the dead of night. Alternatively, he flew to the Benben as a great bird. Papyri from the twenty first Dynasty indicates that Atum himself may have been born from the cry or song of the Bennu bird,

"...that breath of life which emerged from the throat of the Bennu bird, the son of Re in whom Atum appeared in the primeval nought, infinity, darkness and nowhere."

An interesting relationship here begins between Atum, the father, Pharaoh, his spiritual son and viceregent upon the earth, and the Phoenix as a sort of Holy Spirit.

Descriptions of this bird vary between that of the Bennu and Ba. The Ba was depicted as the soul of certain Gods and also deified men. Upon the death of Osiris the Ba leapt from his Heart. Also, the Ba of Atum is said to leap from body to body as it wishes. Ba is strongly identified with the soul, more specifically the magical image or Ruach. Considering the Ba as Atum’s soul, it lands upon the obelisk, or Phallus, and through an act of masturbation it creates the Ennead, all of which symbolize some material feature of both Egypt and the human body. Thus, the creation myth of Atum could be a depiction of a soul self-creating itself into corporeal form on the altar of the sun in Heliopolis, the obelisk, or phallus. The interchangeability of Ba and Bennu as Atum’s soul shines light on this sexual metaphor of re-generation.

A final look at various hieroglyphs that depict Bennu will help understand his connection to the esoteric side of Heliopolis. In Gardenier (G)-32 we see the Bennu standing on one leg in the style of the Ibis. Recall the hieroglyphic translation above that told of Atum’s birth from Bennu’s cry. This may imply that Bennu came before Atum. We find also in various Memphis and late-Kingdom Heliopolitan deviations from the original story that Thoth, the Ibis-headed God, was a pre-existent deity with Atum or Ptah. Thoth, as the Ibis, stood upon one leg. Conversely, in the Theban creation myth it was Amoun who spoke the Ba into existence. The plumage jutting from the back of his head recalls his relation to the Heron.

In G-53 we see the Bennu depicted as having the head of a human. The Ba, again, was the part of the Soul which survived death and would take a trip to a desired location, be it joining the Ka in the Sun in the afterlife (by way of the Obelisk) or, in the case of a King or Priest, the Ba would re-enter the world through another body. At the time of death the Ba would rocket from the heart of the deceased man. The stone in front of G-53 is argued to be the actual Benben stone. (Philae.nu, 2008)

The Bennu’s life is another story. At noon it was said to perch and sing at a cool well. The location of this well differed between the Arabian Peninsula and the temple at Philae. Again, isolation with a well, or source of water, is also a characteristic of a palm tree. Palms, whose roots reach down into the earth, are capable of finding underground sources of water and are therefore indicators of a high water table, a suitable location for a well. Apollo, at either the dawn or noon-tide of his daily journey, would stop at and refresh himself at the well while listening to the Bennu sing. Perhaps his songs bestowed powers to others to cross through the night of death. Apollo’s next destination was Siwa Oasis to the west of Heliopolis in time for dusk. Siwa is the location of Sibyll in Maier’s work, discussed below.

The Bennu’s connection to the Ba of Osiris is seen in this excerpt from the Ani Papyrus:

“I am the great Benu-bird which is in Heliopolis, the supervisor of what exists. Who is he? He is Osiris. As for what exists, that means his injury. Otherwise said: That means his corpse. Otherwise said: It means eternity and everlasting. As for eternity, it means daytime; as for everlasting, it means night.”

Dr. Ogden Goelet, Jr. commented,

“The accompanying caption identifies this bird as benu “the heron,” a Heliopolitan deity associated with the beginnings of creation as a manifestation of Atum, or Re as a creator deity. The Benu is often described as the ‘Egyptian Phoenix,’ an error which may derive from Herodotus, who has transmitted a faulty description of a legend he claimed to have heard from priests of Heliopolis. In the Egyptian legends, however, the Benu is not reborn from his ashes after a fiery death; rather, the Benu made his appearance on the primordial mound when the land emerged from the water, bringing the light with him, a concept fundamental to Heliopolitan religion. As an example of how puzzling the glosses in the accompanying text can be, the Benu is said to be Osiris in one explanation and Osiris’s corpse in the other, two associations the Benu does not seem to have outside this chapter.”

Dr. Goelet’s assumption of the Phoenix's religious role is a little short sighted. Because the Bennu resurrection myth does not appear in Hieroglyphs at hand it does not mean that the myth or ceremony did not occur there. It’s easy to disregard a literal take, but the initiatory or alchemical allegory may have been preserved by the priests and communicated to visitors. This is to say, the Phoenix eucharist may have been given to pilgrims, something like the “salt” or “ash” of the bird being wrapped in dough mingled with resinous gums. The ritual use of the Bennu’s remains may explain why its mummies are exceedingly rare. If such a record did exist in Egypt in writing it would have been subject to early Christian censorship.

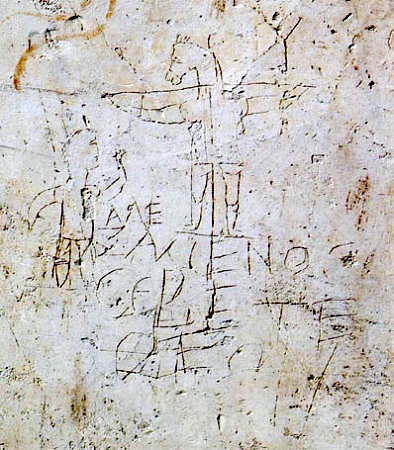

In the fifth century Hieroglyphica Horapollinis, Horapollo lists denotations and connotations of various ancient hieroglyphs, two of which allude to the Bennu. Ch. XXXIV uses a Bennu bird to depict the “soul continuing a long time here.” Ch. XXXV uses a Bennu to depict a man returning home from his travels, this being a sign of prestige and accomplishment. Conversely, an Onocephalus (ass-head) is used to depict a man who has not left his country. This recalls the second century “Alexamenos Graffiti,” which presumably mocked Christians by depicting “Alexamenos worshipping his god,” where Jesus is shown as having the head of a donkey.

As a final note, there is an interesting identification between Horus and Bennu. Nephthys’ relation to the Bennu is similar to her relationship with the infant Horus. She is the protector and nurse of Horus and simultaneously a keeper of the Bennu bird. The connection between Horus the Hawk and the Bennu is seen visually in upper Egyptian temples such as Edfu and Philae where hieroglyphic depictions of the Bennu are composites between the large and lurking crane and the facial features of a hawk. It is possible that Nephthys embodies the role of the Priest preparing the Bennu for resurrection.

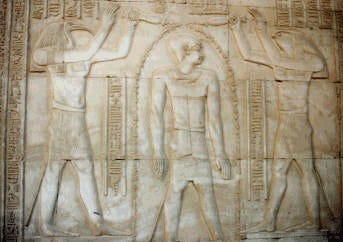

The Miracles of Heliopolis

Much of Heliopolis’ fame is due to the mysterious miracles and magick said to take place there. Many of these were later incorporated into Hebraic or Christian mythos. For instance, depictions in middle to mid-lower Egypt of Baptism are common, usually Horus and/or Thoth pouring Ankhs over someone. Heliopolis was a primary place for this ceremony taking place in the waters of the Nile. This would have been convenient at Heliopolis since many believe the Temple itself was located on an island-hill in the middle of the Nile though the settlement was located nearby to the east in modern day Cairo. A similar arrangement is found with Philae, where the temple and priest residence is located on the island. This is no longer true due to it having been moved for the construction of the Aswan Dam. Another miracle of Heliopolis, which gave it the title “place of multiplying bread,” was when Horus supplied an enormous crowd of people with loaves of bread from only a small supply. During the time of Christ one Roman remarked that Christ’s miracles are nothing impressive and if one truly wants to see magic they ought to visit Egypt.

One ceremony occurred in Heliopolis that is paramount in importance in this essay, and that is the ceremony by which the Bennu is reborn. How this occurs varies between storytellers. The Bennu’s gender is hermaphroditic since it reproduces asexually, like the date palm. However, Herodotus refers to it as its own father. At some point, the Bennu bird reaching the end of its life will do a combination of several actions. Several variations are below recounted that are particular to the Egyptian myth (as delivered by the Greeks).

In the first myth, the Bennu bird gives birth to a nestling Bennu and then immolates itself, hopefully with the nestling at safe distance. The nestling then brings the prepared ashes of its father to Heliopolis where the Priests prepare this into a type of Eucharist and the nestling, upon eating the Eucharist, becomes fledged and inherits the fiery and immortal properties of its parent, reborn a new Bennu.

A second and more popular story is the Bennu bird springing forth from the ashes of its parent. As to whether this takes place in Arabia or Heliopolis is the source of variance. If the immolation did not occur at Heliopolis, the nestling wraps the ashes and delivers them there.

Another variation is who does the preparing. Some account that the nestling itself prepares the Eucharist. Alternatively, this is done by the priests. The subject of preparation is the final one. Several resinous woods and gums are prepared into which the ashes are rolled, forming a ball. These reagents differ between some combination of cacia, myrrh, cinnamon, frankincense, palm leaves, or palm ashes. Palm is almost always present in the story. This is sensible since palm oil is highly flammable and has been used for millennium as both a fuel and a drink. This flammable quality of the palm was relegated to the only palm in the region, the date palm, and this fuel use may be the reason that the Arabic word for the dates (دقلة نور/deglet nour) translates to “dates of light.” The wrapping of the essence inside a ball of something material again recalls Khephra. The dung beetle lays its eggs inside excrement and then rolls that ball some distance to find a water source, in which it lobs the ball. The wetness softens the ball and the dung beetle offspring emerge. Many temple complexes in Egypt include a pool which would be guarded by a statue of Khephra, including Ankh-f-n-Khonsu’s temple at Thebes.

The baby Bennu is not born as a nestling. It is initially a worm or insect. Accounts vary as to whether some process brings it to the next stage or it occurs naturally, but one day later it becomes a nestling. Then, at the height of the second day it is fed the Eucharist of its parent and resumes the office of the Bennu on the third day.

As a side note, this exact incense was used in early Judaism. In Exodus 30 the Altar of Incense is described similarly. It is, in a sense, an obelisk cut off near the base and is the exact size of Crowley’s “double-cube” used in the Gnostic Mass as the Altar of Incense. Of the oil to be prepared and also the incense to be burned thereupon, it is to be of frankincense, myrrh, and calamus (palm leaves),1 respectively life, death and resurrection. In 777 Crowley gives calamus to the Hebrew letter ב/beth, writing “The Palm is Mercurial, as being hermaphroditic.” This altar of incense burns before the veil which is near the Tabernacle and Ark of the Covenant. Naturally, burning a combination of thick resins such as this would leave a pillar of smoke burning before the Ark. The pillar of smoke before the Ark is said to be the force of Shekinah, a type of force or essence of a spiritual community in Judaism.

In Exodus this ritual was performed in the Tent of the Tabernacle. However, when the Jews colonized Salem and constructed the Temple of Solomon the King the ritual was performed therein. Another connection exists in Masonic lore with Solomon’s Temple and the Heliopolis Temple. They were both known for their pillars and both measured 120-cubits across. (Skinner, 1875) Heliopolis’ central pillar, the altar of the Bennu’s sacrifice, was located in the center of the complex. Solomon’s Temple’s Altar of Incense takes the same location. The Egyptian middle-pillar was surmounted by the Benben stone. Late Qabalists name the middle pillar, which is fixed between Jachin and Boaz, Ben (beth-nun), the Son.

The Abrahamic Phoenix

Flamma Dei viuax succenso in pectore veram,

Non adimit vitam, quae renouata viget.2

The Phoenix made some biblical cameos which carried its name into the west via Christianity and Judaism. It was an uncommon subject in Midrashim, but in Christianity it was frequently found in early art. The reason is obvious; the death-rebirth power recalls Christ’s resurrection. The Phoenix complimented another Christian allegory, that of the Pelican. The Phoenix represented Christ’s divine nature (eternity and illumination) and the Pelican his human (charity, sacrifice).

This appearance of the Phoenix in the Book of Job deserves greater attention. As mentioned above, its quality of endurance was considered analogous to Job’s patience and fortitude in dealing with his merciless God. In Job 29:18 we read:

King James Version

Then I said, I shall die in my nest, and I shall multiply my days as the sand.

American Version 1899

And I said: I shall die in my nest, and as a palm tree shall multiply my days.

Complete Jewish Bible

I said, ‘I will die with my nest, and I will live as long as a phoenix.’

The translation of חוֹל/Chul (Cheth-Vav-Lamed) can be “sand,” “palm,” or “Phoenix.”

The midrash Berashit Rabbah discusses the Phoenix’s place in the Garden of Eden. Eve fed the rest of the animals the forbidden fruit, resulting in their exile, yet the Phoenix was the only animal that did not partake, thereby securing its purity and immortality. The Babylonian Talmud relates how Noah’s son Shem tells of his father’s encounter with the Phoenix in the depths of Noah’s ark. (Saggo, 2005)

As for the phoenix, my father discovered it lying in the hold of the ark. ‘Dost thou require no food?’ he asked it. ‘I saw that thou wast busy,’ it replied, ‘so I said to myself, I will give thee no trouble.’ Noah replied, ‘May it be God's will that thou shouldst not perish.” (Sanhedrin, 108b)

The Aggadah, a Midrash intimately describing the Seven Days of creation, discusses the Phoenix as one of God’s odd creatures created on the sixth day. Slight deviations from the regular myth are obvious:

Among the birds the phoenix is the most wonderful. When Eve gave all the animals some of the fruit of the tree of knowledge, the phoenix was the only bird that refused to eat thereof, and he was rewarded with eternal life. When he has lived a thousand years, his body shrinks, and the feathers drop from it, until he is as small as an egg. This is the nucleus of the new bird.

The phoenix is also called "the guardian of the terrestrial sphere." He runs with the sun on his circuit, and he spreads out his wings and catches up the fiery rays of the sun. If he were not there to intercept them, neither man nor any other animate being would keep alive. On his right wing the following words are inscribed in huge letters, about four thousand stadia high: "Neither the earth produces me, nor the heavens, but only the wings of fire." His food consists of the manna of heaven and the dew of the earth. His excrement is a worm, whose excrement in turn is the cinnamon used by kings and princes. Enoch, who saw the phoenix birds when he was translated, describes them as flying creatures, wonderful and strange in appearance, with the feet and tails of lions, and the heads of crocodiles; their appearance is of a purple color like the rainbow; their size nine hundred measures. Their wings are like those of angels, each having twelve, and they attend the chariot of the sun and go with him, bringing heat and dew as they are ordered by God. In the morning when the sun starts on his daily course, the phoenixes and the chalkidri sing, and every bird flaps its wings, rejoicing the Giver of light, and they sing a song at the command of the Lord.

(Ginzberg, 1909)

The cognate symbol of the Bennu as the Ba and Dove as the Holy Spirit is unmistakable. They were both portrayed as a flame in their greatest antiquity. The Shekinah, in a way the Jewish Holy Spirit, would descend as a tongue of flame on the heads of the faithful during Passover. Similarly, the Shekinah was conjured before the Ark of the Covenant by means of the same resins and incenses used to preserve the power of the Bennu. The Ba itself was depicted more as a ray of sunlight rather than a flame, but the Ba as the Phoenix and Bennu and their connection to fire still provides a strong connection with the dove as the Holy Spirit. The dove was also present on the ark and was one of Noah’s two birds that he released to find dry land. It returned with an olive branch, but the raven did not return.

A further connection with the ceremonial invocation of Shekinah or Spiritus Sancti and the Phoenix is the respective celebration of Passover or the Last Supper which roughly fall at the same time. The Last Supper became celebrated regularly in the form of the Agape Feast, the revelry of which was said to invoke the Holy Spirit as a comfort for the darkness of Christ’s death and promise of his resurrection. The sex-magical character of the Agape feast hearkens back to the Old Testament where Abraham was said to be in the presence of the Shekinah during sex, resulting in the prophetic birth of Isaac. Just as the Bennu would consume a Eucharist to renew its life the early Christians would consume Christ’s flesh and blood in the Agape feast to remind themselves of Christ and his covenant, the promise of everlasting life.

Christ had an interesting ancient connection to phoinos’ alternative translation, the palm. Recall that the Phoenix would use palm fronds or oil in its immolation and that palm fronds would be used to embalm its ashes for the Communion to follow. Palm fronds were used in ancient times during various ceremonies of the Levant and Near East. They were used to mark the doorways of tombs of holy men, prophets, and saints, Mohammad had built his home from palms, they were waved during celebrations and festivals, Romans granted palm fronds to victorious soldiers, and palms were used to cover the grounds of armies returning home victoriously. Using palms to cover someone’s path also welcomed Dionysus in a city just as they did Jesus in the Gospel of Mark.

Two Roman Catholic ceremonies mark the use of palms and their relation to Christ. Palm Sunday marks the Sunday before his Crucifixion and his return to Jerusalem amongst exclamations of the savior having come to free the Daughter of Israel, a title of Shekinah. Palms thrown before his path recognizes Christ as a redeemer, savior, conqueror, and Saint. Another Catholic holiday using palms marks the beginning of the season of Lent. This is Ash Wednesday, during which time Christians take the ash of palm fronds (traditionally being the palms of the previous year’s Palm Sunday) and receive the Mark on their forehead. While marking the Christian the priest cheers them up, saying, “remember that you are dust and to dust you shall return.” Ash Wednesday initiates 40 days of repentance, sacrifice, and asceticism. These 40 days are related to Christ’s time in the desert during which he underwent the same meditation.

The Phoenix’s primary color being red, indicating fire and blood (phoinos), this is also the liturgical color used for the Feast Days of Palm Sunday, Pentecost, Good Friday (when Christ died), and the death-days and martyrdom days of Popes, Cardinals, and Saints.

Other connections between the Phoenix and early Christian symbolism are likely. Many authors speak of its use in Christian symbolism, but few provide physical references. One catacomb called St. Miltiades dating to the 2nd Century has “an impressive carving: a phoenix with rays and an aureole surrounding its head.” (Christian, 2004)

It seems as if the Phoenix took an extended leave from the west after this late Roman period. But when Europe reawakened to its Hellenic heritage through the reintroduction of classical literature during the Renaissance the Phoenix made a strong come back. The Phoenix was preserved on heraldry and art, but the primary renewed interest probably came from Renaissance revival of Hellas and the Renaissance church's appeal to Midrashim and qabalah for elaboration on the Old Testament. Both of these currents fed into what became Rosicrucian circles and contributed to the genre of hermeticism.

The Hermetic Phoenix

Early Rosicrucians are responsible for the revival of interest in the truly esoteric and an attempt to subvert religion by reviving the study of the first principles of the ancient mystery schools. The Renaissance was a time of earnest exploration of the mysteries, with what little they had available, and western spirituality ended up caught in between subjectivism and humanism. However, some believed that the objective integrity of the mysteries could be preserved through initiation and allegories. This paradigm was called Hermeticism and its proponents the Rosicrucians.

There are two Rosicrucians particularly worth noting for their contribution to the Phoenix myth. These are Christian Rosenkreuz (whose existence and authorship are irrelevant for present purposes) and Michael Maier. Their canonization is evidence of their importance in a later development of the Phoenix myth, and a return to its ritual import, in the context of Magick.

Bear in mind while reading the following alchemical dissections that, following an early Hermetic maxim, anything which displays a certain power is believed to be capable of bestowing that power by virtue of its components’ consumption or ritual use. For instance, bread’s ability to “rise” is conferrable by “risen” bread’s consumption. Also, red wine's quality is related to its exposure to the sun, making good red wine capable of transferring that to its drinker. Similarly, the Phoenix’s feathers or ashes were believed to possess this quality, and their ritual use in ceremonies such as Rosencreutz’s Chemische Hochzeit intended to emulate its power. Whether the technical details provided by alchemists allude to a secret recipe for a decoction isn’t really the concern of this essay as much as is the symbolic and magical interpretation.

Rosenkreuz is the apocryphal founder of the Fama Fraternitatis, the Rosicrucians. Several works ascribed to him are considered the founding documents. One of these, published in 1616, was the Chymische Hochzeit, or Chemical Marriage. A fast-paced and dense work of layered symbolism would be difficult to summarize here, but several editions of this work are available for a free reading online. It tells a story of an old and wise man, stern in his faith and enlightened through his love of God, and his seven adventurous days leading up to a Royal Wedding.

Nothing about this week is normal and many feats are required of Rosenkreuz to test his spiritual mettle. During Day 3, when Rosenkreuz was set at liberty to tour the Castle, he came upon many treasures whose experience he described as communicating more than all the books in any library. He says, “there in the same place stands also the glorious phoenix (about which, two years ago, I published a particular small discourse),” but he is not so kind as to name this small discourse. Whether this is the Phoenix itself or an image is not said, but 2 days later, during Day 5, he mentions a Sepulcher again, saying “Herewith my companions were deceived, for they imagined nothing other but that the dead corpses were there. Upon the top of all there was a great flag, having a phoenix painted on it, perhaps the more to delude us. Here I had great occasion to thank God that I had seen more than the rest.” Rosenkreuz is the hero of this tale in managing to accomplish the resurrection of the King and Queen at the end of Day 6. Day 6 involves an alchemical transformation of a little bird which Rosenkreuz presided over. Perhaps something was revealed to him at one of these Sepulchers that gave him the insight to perform this operation correctly.

Day 6 contained an adventure through a tower. On the third floor Rosenkreuz and his companions opened a globe and therein found an egg which was ushered off by the Virgin. On the fourth floor they found the egg again and it had completely matured by some process of which Rosenkreuz was unaware. The egg hatched and a healthy, bloody, and undeveloped nestling emerged. After being fed blood of the beheaded King and Queen it fully fledged with black feathers. A second bloody meal caused it to molt and grow snow-white feathers, and lastly a third feeding caused his feathers to gain some multi-colored luster. On the fifth floor a heated bath of water and white powder was prepared for the bird. Its feathers were boiled off, but the bird was unharmed by the heat. It was set at liberty, and the feathers had turned the water into a type of blue paste which the naked bird was then painted with, all save its head. On the sixth floor an altar was prepared upon which was a serpent. The bird pecked at the serpent, killing him, and was then fed a draught of its displeasing blood. The bird then willingly gave its head to be removed, and after the head was cut off (from which no blood poured) the breast was opened and a blood flow as gorgeous as rubies spurted from its corpse. Its corpse was burnt and the ashes thereof were taken to the seventh floor where they were prepared into dough and baked. From the oven emerged two lifeless homunculi that, when fed the blood of the deceased bird, grew to full size. A short while later the decapitated King and Queen had reincarnated in the animated flesh made by the components of the little bird’s sacrifices.

Several aspects of this transformation recall the myth of the Bennu. A bird’s ashes are prepared into a Eucharist to a powerless image of itself and thereby it is reborn. The Phoenix, through its ashes, seems to work in concert with a Pelican nature, through the blood of its breast. Adam McLean (1979) provides a description of the alchemical bird’s transformation which seems to soundly follow the description provided in Day 6. He describes a “sequence, one which occurs in various sources: Black Crow - White Swan - Peacock - Pelican - Phoenix - as these correspond to a developing inner experience which involves a progressively deepening encounter with the inner spiritual dimension of our being.” In short it is a process of purification through sacrifice resulting in a perfect and immortal quality, the Phoenix. This Phoenix would Hermetically possess this process of resurrection and its ashes would be capable of bestowing this power, thence the resurrection of the King and Queen. Their blood was consumed by the “bloody and shapeless” bird and ultimately the bird’s blood and ashes were combined into a body and blood of the resurrected King and Queen.

It is unfortunate that Rosenkreuz does not cite where he previously discoursed on the Phoenix. The Chemical Marriage, Fama Fraternitatis, and Confessio are the only works ascribed to him; however, another Rosicrucian writing around the same time did wax on the Phoenix much more.

Michal Maier was a German intellectual and physician whose cosmopolitan education contributed much to Rosicrucian literature. In 1617 Maier published an alchemical emblem book titled Atalanta Fugiens which depicted etches of various alchemical processes and a commentary in lucid prose. A few of these mention the Phoenix and are great descriptions of its alchemical role.

Emblem-33, “The Hermaphrodite, lying like a dead man in darkness, wants Fire,” depicts a hermaphrodite with two heads lying on a funerary pyre. The full moon illumes the spiritual darkness of the hermaphrodite’s death as Maier describes nature’s desire of external heat to ignite the internal flame. The Phoenix is used as a metaphor. Recall that the Phoenix itself is neither male nor female, and because its offspring is born of itself then it can be considered Hermaphroditic.

“One only Phoenix there is, which is restored by Fire, renewed by Flames and revived out of Ashes; and this, being known only to the Philosophers, is burnt and restored to life, whatever others fabulously may report of a certain Bird that never yet was seen or had any Being. Likewise, the Hermaphrodite of which the Philosophers speak is of a mixed Nature, Male and Female, one of which passes into the other by the Operation of Heat. For from a female it becomes a male, which ought not to seem strange in the Work of the Philosophers.”

(Maier, 1617)

The allusion of the female becoming male in the Philosopher’s Work is a plausible reference to the Great Work, the transmutation of metals or the infusion of the feminine soul with masculine spirit. The depiction of the soul as a hermaphrodite is not uncommon and implies the soul itself contains the seed of its own manifestation and rebirth. German Qabalism and mysticism were strongly influenced by selective interpretations of common Qabalism. The Hebrew word for Soul is feminine, as was the Hebrew word for Shekinah, a type of Sophia Perennis or Minerva Mundi. The various messianic figures such as Logos, Christ, Lucifer, etc., were traditionally portrayed as masculine. These two genders in conjunction were seen as being hermaphroditic, and their union initiated transformation of the soul’s nature from feminine to masculine.

By the increase of heat the genital parts are thrust out of the Body: for seeing a Woman is much colder than a male, and has those parts hidden within which a man has outwardly… After the same manner it is with the Philosophers, for by the increase of heat their woman becomes a man; that is, their Hermaphrodite loses the female sex and becomes a man stout and grave, having nothing in him of Effeminate Softness and Levity.

Alchemy's allegorical nature makes it frequently difficult to discuss, dissect, and digest. Key words and themes are noteworthy. In this excerpt, the theme of “coming out” and “hardening” is critical. As we will see later, the application of heat (via flame or Sulfur) hardens Mercury (making it “fixed”) and is a reference to making something substantial rather than incorporeal. Other period descriptions of the hermaphrodite even say it is three genders, referring to salt, sulfur, and mercury. Gender here simply means type or qualia.

As a final point it is noteworthy that the Emblems in Atalanta Fugiens describe a very long transformation and the summation of this part is,

“For Heat sequesters and separates the superfluityes of Moisture and will Establish the Idea of the Philosophickal Subject, which is the Tincture.”

Ah the tincture! Often described as a variety of colors and consistencies, blue or red or white, or as a paste, powder, or fluid, a tincture represents some material which can initiate some sort of chemical change, often to metals, at least allegorically. However, the tincture also has to be derived from the components. The little bird of Rosenkreuz underwent a terrible series of ordeals where its components were divided and coagulated into a final product. Its plumage, blood, and ash were all recombined after being separated and purified in order to make the vital medicine. The Secret Symbols of the Rosicrucians mentions the Hermaphroditism of the Phoenix in an alchemical context as being a combination and careful balance of various alchemical polarities. Quoting,

“The same Salt-Mother of the elements is the nitrous, aluminous and spiritual gumosic water, earth or crystal, which has Nature in its womb, a Son of the Sun, and a Daughter of the Moon. It is a Hermaphrodite, born out of the wind, a phoenix living in fire, a pelican, reviving his dear young ones with its blood; the young Icarus, drowned in the water, whose nurse is the earth, whose Mother is the wind, whose Father is the fire, the water her caretaker and drink, one stone and no stone, one water and no water, nevertheless a stone of living power and a water of living might; a sulphur, a mercury, a salt, hidden deep in nature, and which no fool has ever known nor seen.”

(Rosicrucian, 1785)

Maier mentions the Phoenix again in passing in his description of Emblem-43, titled “Give ear to the Vulture’s words, which are in no wise false.” The Vulture is not the sole subject of this Emblem, but instead Maier discusses the “philosophic bird.” He describes certain birds as being able to speak so as to pronounce their nature and that which they govern. Also, certain birds possess the power to self-fertilize. The vulture’s impregnation by wind in Egyptian mythology comes to mind.

“He conceives from himself (for so Rosarius towards the End. ) And he is the Dragon who marries himself and impregnates himself and brings forth in his own Season. And Rosarius to Sarratanta, " And that is the Serpent, Luxuriant in itself, impregnating itself, and bringing forth in one day. " It lives and endures a very long time, and multiplies itself. For what Virgil writes concerning the Phoenix agrees likewise to this, for it is the same Bird… It is very difficult to climb the nest of this Bird. It fights with the Mercurial Serpent, and overcomes it, that is Sol. With Luna it is conceived by the wind and carried in its belly, and born in the Air.”

This is the second place in the referenced Rosicrucian literature where the phoenix is juxtaposed to the serpent. The Phoenix is given a quality of Sulphur and the snake that of Mercury. As the snake possesses some immortal quality, Rosenkreuz’s little bird drinking the blood of the snake before its death seems to be a preparation of sulphur by fixed mercury to preserve its life through death.

Before going on to Allegoria Bella it is worth discussing the Phoenix’s fire as an alchemical agent. In Secret Symbols of the Rosicrucians, at the end of Book I, three fires are mentioned in presiding over the uniting of moist and dry. The first fire is the outer fire, “which the Artist or watchman maketh, which the Wise Men call ignem frontem, upon which Regimen dependeth the safety or the ruin of the entire Work.” The second fire is born of the Phoenix,

“…the nest wherein the Phoenix of the Philosophers hath its abode, and hatcheth itself therein ad regenerationem. This is nothing else than the Vas Philosophorum [the way of the philosophers]. The Wise Men call it ignem corticum [fire of the mind], for it is written that the Phoenix bird collected all fragrant wood whereon it cremateth itself. If this were not so, the Phoenix would freeze to death and it could not attain to its Perfection. Sulphura Sulphuribus continentur [sulfur contains sulfur]. For the nest should protect, assist, cherish and keep the brood of the bird unto the final end.”

But, there is a final and third fire which exists hidden and secret with Mercury.

In the essence of the Mercurii is a sulphur which finally conquereth the coldness and the moisture in the Mercurio. This is nothing else than a small fire hidden in the Mercurio, which is aroused in our Mineris, and in the fulness of time it absorbeth the coldness and moisture in the Mercurio or removeth them, and that is also said about the fire.

Thus the combination of the Phoenix’s sulphur and Serpent’s mercury results in perfected sulphur. (Rosicrucian, 1785) In Crowley’s Atu XIII, Death, we see a process of transformation from cold mercurial fish to serpent and then to the vaporous eagle, but the eagle foreshadows the phoenix which is being prepared in the cauldron of Atu XIV, Art. The three trumps that precede Art are XI Lust, XII The Hanged Man, and XIII Death; respectively, sulfur, salt and mercury. Art is followed by XV, The Devil, ie Baphomet who is in the mystic aviary is indicated by the Double Headed Black Eagle.

Allegoria Bella

Published in 1617 by Maier, Allegoria Bella is an alchemical classic that describes the author in an existential funk much like that of Goethe’s Dr. Faustus, who also had troubles with his conscience over safe and effective potions. Dissatisfied with the burden of mundane life, Maier decides upon a quest,

for I had heard that there was a bird called Phoenix, the only one of its kind in the whole world, whose feathers and flesh constitute the great and glorious medicine for all passion, pain, and sorrow; which also Helena, after her return from Troy, had presented in the form of a draught3 to Telemachus, who thereupon had forgotten all his sorrows and troubles. This bird I could not indeed hope to obtain entire, but I was seized with an irresistible longing to become possessed of at least one of its smallest feathers.

His inspirational quest to find a cure for melancholy would take him across the world. And as an allegorical piece, each element in the story represents some type of alchemical change.

For Maier, adventure accomplished the same transformation as the alchemical process. Maier “regarded his earthly existence as a spiritual journey... and a reflected image of the alchemical process itself.” (Tilton, 2003)

“The plan of my journey was determined by the relative quality of the elements which the different parts of the world represent, i.e., Europe stands for earth, America for water, Asia for air, and Africa for fire; and earth cannot become air except through the medium of water; nor can water become fire except through the medium of air. I determined, then, to go first to Europe, which represents the grossest, and last to Africa, which represents the most subtle element. But my reasons will be set forth more clearly as I come to speak of the different parts of the world.” -(Maier, 1617)

Europe is considered earth due to earth possessing a large proportion of the other elements, the result of which contains some method for the production of Heroes and Kings. He calls Europe a Virgin Lion, “Virgin because of her beauty and spotless purity; a Lion because she has conquered others, but has never herself been conquered.” Maier expected to find the Phoenix in Europe since Europe represents the sun upon the earth, but instead he was met with mockery by Europeans. He rebutted, saying that casual searching would never yield this greatest of treasures and that he must seek the Phoenix as the King his Queen or Princess her Prince. Europe seems to be here characterized as the alchemical Green Lion, the spontaneous generation born from sulphur and stone, the first sulphur and first matter. This sulphur, Maier’s ambition born of melancholy, must be purified by the prepared solvent.

America is the next destination, to which he sailed on a ship with an Eagle as its prow. In Emblem-46 of Atalanta Fugiens Maier describes the eagle as being sacred to John and the two eagles which circumnavigate the globe (east and west) to Sulfur and Mercury. Maier’s hope to find the exotic Phoenix among the other exotic birds of America led to disappointment. Instead he found “a stupid kind of people” and became engaged in the proper breeding of mules. [Here I’d like to point out that by America he seems to mean Brazil.] There was also much discussion of some water in America being capable of making Gold malleable, and also the transformation and separation of other elements, and the extraction of the “red Tincture” from quicksilver (mercury). Maier compares the soil of America to that of Peru, “Now all these are different kinds of mineral earth: the black earth, if mixed with water or wine, makes an excellent ink, the red soil is said to be the ore of quicksilver, and the Indians paint themselves with it.” Maier brought back with him a piece of black wood. This black wood may represent a fixed or solid form of sulphur, resulting from Europe’s Green Lion and Virgin Earth being transformed by American’s watery solvent.

Asia, or specifically Asia Minor, yielded an encounter with Jason (of the Argonautica) who instructed him as to the acquisition of the Golden Fleece. Inspired by this, Maier prays to Christ for assistance in his quest. He then finds himself in a city where many people are ranting about returning to paradise, so he follows his nose and discovers a pearl which he believes to be an important component of this Medicine he seeks. After discovering a statue of Mercury, he decides to continue his trek to Africa.

In Africa, by which he means Egypt, he sought the Sibyll, a prophetess, who answered his question as to the Phoenix’s location with the following,

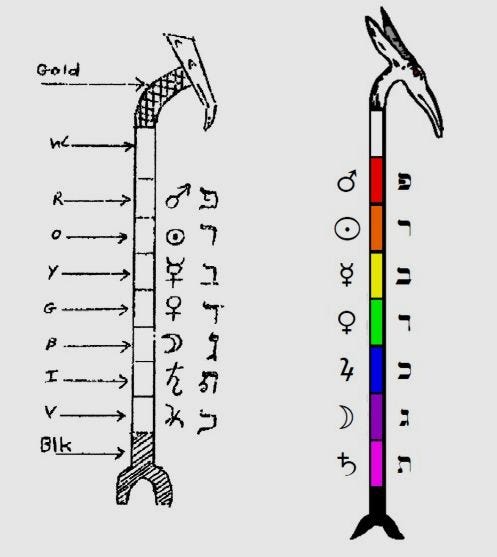

"The object of your search is a great and glorious one; doubt is the first stage of knowledge, and you have also come to the right place and the right person. For the country in which you now find yourself is Araby the Blest, and nowhere else has the Phoenix ever been found; moreover, I am the only person who could possibly give you any definite information about it. I will teach you, and this land will exhibit to you, the glad sight of which I speak. Therefore, listen to my words Arabs the Blest and Egypt have from of old rejoiced in the sole possession of the Phoenix, whose neck is of a golden hue, while the rest of its body is purple, and its head is crowned with a beautiful crest. It is sacred to the Sun, lives 660 years, and when the last hour of its life approaches, it builds a nest of cassia and frankincense, fills it with fragrant spices, kindles it by flapping its wings towards the Sun, and is burnt to ashes with it. From these ashes there is generated a worm, and out of the worm a young bird which takes the nest, with the remains of its parent, and carries it to Heliopolis (or Thebes), the sacred city of the Sun in Egypt. Now, this whole tale which you find in the books of the Ancients is addressed to the mind rather than to the ear; it is a mystical narrative, and like the hieroglyphics of the Egyptians, should be mystically (not historically) understood. An ancient Egyptian writer tells us that the Phoenix rejoices in the Sun, and that this predilection is its chief reason for coming to Egypt. He also relates that his countrymen were in the habit of embalming the Phoenix if it died before its time. If you therefore regard this tale as an allegory, you will not be far wrong; and you know that the flesh and feathers of this bird were of old used in Heliopolis as a remedy for anger and grief…Nevertheless, the most important part of the enterprise must be performed by the toil of your own hands. I cannot describe to you in exact and unmistakable terms the place where the Phoenix lives, yet I will endeavor to make it as plain to you as I may. Egypt, you know, owes all her fertility to the Nile, whose sources are unknown and undiscoverable; but the mouths by which it is discharged into the sea, are sufficiently patent to all. The fourth Son of the Nile is Mercury, and to him his father has given authority to shew you this bird, and its Medicine. This Mercury you may expect to find somewhere near the seven mouths of the Nile; for he has no fixed habitation, but is to be found now in one of these mouths, and now in another."

Maier then took to searching the mouth of each of these rivers, which he believed to relate to the seven planets. He found Mercury in none of them, but upon retracing his steps he found Mercury. Dr. Tilton (2003) posits the Tanitic mouth was Mercury's home, being the fifth mouth which was Mercury's position in relation to the Saturn in Maier's cosmology. This was the mouth where the locals actively denied Mercury's presence rather than feign ignorance - a blind. Mercury directed him to the Phoenix’s location, but the Phoenix was temporarily absent. Suddenly, Maier left to his homeland with the knowledge he had obtained. His alternative was to tack on a mere three weeks to his quest which up to now had already exceeded a year. Why did Maier not wait?

Dr. Tilton posits the answer can be found in the author referenced by the Sibyl, “Horus Apollo”, or more commonly known now as Horapollo. His Hieroglyphics of Horapollo, written in the fifth century, attempts to explain certain motifs in Egyptian hieroglyphs without much concern with literary accuracy. When he says the Phoenix is used to indicate “a traveller who returns from a long journey to his native land” (Horapollo, 1598) we can assume that Maier, in his return, actually did find that Phoenix in a more subtle way. One reading is that Maier's “return” to Egypt was the very discovery of that Phoenix where he is “mystically served with funerary rites.” Alternatively his achievement was the return to his own home, Germany, as if he discovered the Phoenix as himself as he was back in a familiar place but with a renewed vitality, like the Phoenix awakening within a new fledgling.

This theme of returning home is also foreshadowed in Maier’s opening, quoted above, where he refers to whatever medicine Helen gave Telemachus. This is a reference to The Odyssey,4 where Odysseus and his Argonauts (many of whom are canonized by Crowley for the Gnostic Mass) merely want to return home. In Greek this is νόστος/nostos, whither nostalgia, and the length of Odysseus’ longing is the strength of his glory when he arrives. In alchemy the idea is that materials are encountered in impure forms and need to be refined in order to be worked. Their gradual purification is their return to some pure state, their noumenal home, but it requires ardor, grace, and skill. Just the same the mystical adventure has been described as a return home, be it to the womb of supernal Babalon as a Babe of the Abyss or a redemptive repairing to the Garden of Eden.

Further on the Alchemy of the Phoenix

Alchemical literature between the 15th and 17th century was at its aleatory height, such as described by Crowley in his 1925 essay “The Method of Thelema.” The Phoenix was frequently evoked, sometimes to anoint research with Christian overtones but to many it was the central element of alchemy. Maier was one such alchemist to explore this mystery and he scorned contemporaries for their naïve understanding. Maier argued that the discovery of the origin of the phoenix was crucial for unlocking its secret. The tree is a surprising source of origin for the Phoenix. Maier describes one type of duck borne from a tree on the Orcanian Isles. This tree produces a fruit which then falls into the water. From this fruit a duck is born. Maier compares this duck to the Phoenix, saying,

But, that our tree–born bird appear not to our reader unique and sole among the vast host of winged beings, let us place him in the company of the Phœnix, that bird of fire, veritable nestling of the Sun, Vulcan's nursling — to whose birth hasten all gods and goddesses thronging the chapels of Egypt, that they might shower it with gifts upon its birth day.

-Maier, Tractatus de Volucri Arborea

This description continued into a chemical one. Maier proclaims the Phoenix's residence in Arabia was due to the riches of their temples which contained many rare metals. The description is here cited, but bear in mind Maier's obsession with the sun as the true god and the Phoenix as a representation of that sun.

“Indeed, Nature first engendered In Araby a pupa, the seed from which the full–blown bird arises. For should one dispute to know which came first, the egg or chicken, let it then be answered that the first bird was created by God from nothing, with no pre–existent seed, and came from no egg[...] The celestial Sun produces the larva by a putrefaction in its own substance which is procured by Mercury. Thence, Mercury, Vulcan, and Apollo, who is the Sun, engender that Orion from the stagnation of urine or, rather, semen, enwrapping it in an cow–hide[...] The larva is thus first born in Araby from the viscous matter of Mercury by the operation of the Sun's heat, and in the same place, by the ministrations of Vulcan, artist of Egypt, it is transmuted into the Phœnix itself... The Tincture is Phoenician or Tyrean in colour and stems from a subject which is burnt and reduced to ashes, which ashes are consecrate to the Sun and both celestial and terrestrial, because of the solar child hid within them, and which resume life or, rather, their multiplication, in the manner of a propagation. They are thus never extinguished but, like fire, augment unto infinity by means of their self–nourishment.”

In Commentaire sur le Tresor des tresors de Christophle de Gamon (1610) the Phoenix is posited as being a symbol of the purified sulfur. Henri de Linthaut says,

“Wishing to veil this Treasure of Treasures, and its augmentation, the Poets invented the Phœnix which, dying, produces always of itself another of its species, ever taking birth, dying and being reborn within the fire. Such that by this fable, they wished us to understand how the real Phœnix, this divine Elixir, is born of fire, that is to say of Sulphur: and is transformed into ashes in the fire, when the work once again resolves into Black Sulphur: and revives in the fire on becoming the Red Sulphur or Red Elixir. Thus it is always one and the same bird, sacrifices itself to the rays of the Sun, which, in our fermentation, means that it is withdrawn by the Gold, or Sun of metals. It is also, say our Poets, this Phœnix that asserts itself as animal, for it vivifies all things, and also vegetable, in that it believes in quantity and virtue; and mineral with regard to the material from which it is born. This also is the bird who once born, cries that the artist shall never leave him, and he never quit the artist; thus is its pyre built, that it may burn itself, be reborn and multiply unto infinity.”

The Phoenix has been identified with both the white tincture and red tincture, the purification of mercury and sulfur respectively. This alchemical process was also described as an interaction between other mystic aviary. The Crow-to-Phoenix description given above is one example, but its focus on the exoteric symbols and meaning reduces the importance of the subtle process described by earlier authors. Clovis Hesteau de Nuysement in 1620 composed a poem describing the Phoenix:

In the same forest, my eye was carried

to a nest wherein lay Hermes' two birds.

One was attempting to take flight,

while the other prevented his escape;

Thus the one holds back the other, and never leaves it.

Above this nest I saw upon a branch,

Two birds locked in combat, destroying each other.

One the colour of blood, the other was white,

And, dying, both assumed a happier form.

I saw them transform into snow white doves,

And then, together, become one, single Phoenix,

Who, like unto the Sun, on brilliant wings,

Leaping aloft from that Park, betook himself unto the Empyrean heights.

This metaphor was taken by P. J. Farbre (in Panchymicum, 1646) as a typical illustration of the interaction of the red and white eagles. These two eagles recall Maier's eagles of the East and West. Their mutual murder results in the consumption of one another's blood and from this intermingling is borne two doves. These doves unify, and thence is born the Phoenix. Farbre goes on to compare the Phoenix to a silk worm whose metamorphoses in its cocoon gives birth to a new creature. “The virtue of this seed can never be destroyed in any manner[...] and cannot be annihilated in anyway. Were it otherwise, and if nothing of ourselves subsisted, there would be no hope that we might, one day, raise ourselves from our own ashes, for resurrection is not a creation but the renewal of the body from one that existed before.”

Farbre further gives the ashes to a salt, saying,

Indeed, the fire consumes all that is thick and foul, and nothing is left but the ashes containing a fixed and pure salt within which the various colours dwell. These are communicated to the reincarnating bird without effort, for this salt in the ashes of the Phoenix, in consequence of its immolation, is its true seed, whence, as from an egg, a new Phoenix is born. And also that extremely long. […]

The Phoenix... is the salt of the Wise, and, thus, their Mercury; it is Bazil Valentine's salt of glory, the albrot salt of Artephius, Trevisan's double Mercury, which is the philosophic embryo, and the bird born of Hermogenes; it is dry water, fiery water, and the universal Menstruum, or Spirit of the Universe... it is itself the sugar of the Moonwort, the spirit and soul of the Sun, the bain-marie, where King and Queen must bathe.

[...] it contains within it the unnatural fire, the moist fire, the secret fire, occult and invisible.

Some posit the Phoenix itself is the Elixer, others that its role is the multiplication of the Elixer (of life). Giovanni Bracesco posits that “our Jupiter” is derived from the Phoenix's ashes which, when mixed with the Elixer, multiplies it.

Paracelsus posits this multiplication, and the role of the Phoenix, in relation to the Iliastric soul to the Cagastric body, saying,

.The Iliastric soul, on the other hand, is so made that neither heat nor cold may harm it, but that heat is its life and nourishment, its air and pleasure, its joy and delectation. In other words, the salamandrine Phœnix lives in the fire and is the Iliastric soul in man. This being so, the soul also growing in the body of man, and rooting itself in the heart, but, like a tree and its branches, separating its branches into the blood and veins where dwell the spirit of fire and fire itself, there is the soul upright upon its throne and its dwelling in the blood and the veins. So much for the Phœnix.

-Paracelsus, Liber Azoth (1591)

The identification of the Phoenix with the Iliastric soul is an important recollection of the Bennu as it relates to the Ba. The Ba's reentry into the body carried the soul of a past life into a future life. The strength of that Ba, and also of that Iliastric soul, determined how well it survived the intermediary period before reincarnation. The Elixer of Life or Phoenix Tincture as the strengthening of this Iliastric soul, and so to Crowley's use of the Phoenix in magick.

The Phoenix of Aleister Crowley

Neglect not the daily Miracle of the Mass, either by the Rite of the Gnostic Catholic Church, or that of the Phoenix. Neglect not the Performance of the Mass of the Holy Ghost, as Nature herself prompteth thee.

-Aleister Crowley: Liber Aleph, De Cultu

Crowley mentions the Phoenix several times in more esoteric works, particularly The Book of Lies, Liber 333. Crowley’s understanding of the Phoenix is derived from both the historical context, in the case of the Bennu bird, and his studies of alchemy. Rosenkreuz and Maier were both canonized by Crowley in his Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica, suggesting they were influences in the symbolism of the Gnostic Mass, mysteries of OTO, and also Crowley’s magical and alchemical philosophy. Crowley declared each of these men in Liber 52 as having constituted originating assemblies of the OTO.

In The Book of Lies there are several chapters that deal with the phoenix, each of which are one page of cryptic prose followed by one page of comment. Most obviously there is The Mass of the Phoenix, chapter 44, but also chapter 62, Twig?, chapter 11, The Glow-Worm, and chapter 16, The Stag-Beetle.

With The Mass of the Phoenix, as with all chapters in The Book of Lies, its number, 44, reflects its subject. This number is “the special number of Horus; it is the Hebrew [word for] blood, and the multiplication of the 4 by the 11, the number of Magick, explains 4 in its finest sense. But see in particular the accounts in Equinox I:7 of the circumstances of the Equinox of the Gods.” The Hebrew word for Blood is דם/dem and its enumeration 44. Daleth is the Empress, Venus, who plays a subtle role in the Chemical Marriage, and mem is the Hanged Man, appropriate to water and resurrection. And in contrast to the Emperor’s Ram, the Empress sits with a Pelican that feeds her nestlings. Her shield contains the same double headed bird as the Emperor; however, the Empress’ bird is white. Duquette comments that these two-headed eagles represent the white tincture and red tincture respectively. Their two-headedness represents androgeneity, therefore the balance of the forces within the tincture. Daleth’s position on the Tree of Life is the gate, or door-way, so in conjunction with mem and dem it may be suggestive of blood flow or menstrual blood, an interpretation of Maier’s Emblem-33 (by virtue of the full moon). As noted earlier, Job 29:18’s choll enumerates to 44 as well. Choll is the Hebrew word for both “sand” and “Phoenix”. Lastly, the Greek word Φοίνικος/Phoinikos is the color “sun-red” and several of the above alchemists posited the Phoenix produced the “red tincture.”

During the Mass of the Phoenix, the Magician cuts their breast to draw blood to soak a cake. The significance of blood to the Phoenix myth and Mass is obvious by virtue of the Phoenix’s compliment in the Christian context, the Pelican, and by blood’s association with sacrifice. Crowley explains, “The word ‘Phoenix’ may be taken as including the idea of ‘Pelican’, the bird, which is fabled to feed its young from the blood of its own breast. Yet the two ideas, though cognate, are not identical, and ‘Phoenix’ is the more accurate symbol.” The natural question is: accurate in reference to what? Their role in alchemy is largely complimentary; the Phoenix is Christ’s divine nature, the Pelican his human. The Phoenix performs the process of spiritual perfection and rejuvenation, the Pelican performs a sacrifice by which its offspring are fed. The paternal Phoenix lives on, father to son. The maternal Pelican lives on in its offspring. In cases such as the bird transmutation (above) and Rosenkreuz’s phoenix-pelican sacrifice to revive the King and Queen it is obvious how the two were seen to work in conjunction, the blood and the ash having distinct purposes. The overlapping roles of the mystic aviary is a confusing theme with Crowley.

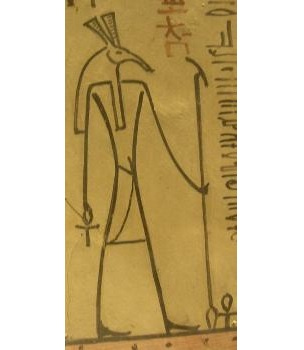

The phoenix-pelican connection is not the only link between the phoenix and blood. In the Golden Dawn’s Adeptus Minor initiation the 2nd Adept carries the Phoenix Wand. It is also the 2nd Adept that dips the dagger in a cup of wine and draws crosses over the head, feet, hands and heart of the aspirant, simulating Christ’s wounds. The heart is the last place symbolically cut, in silence. The Phoenix Wand is designed to resemble the Uas (wꜣs, Ouas) Scepter, though many argue its head is actually that of the Set animal. It’s perhaps best known by Thelemites as being carried by Horus, such as on the Stele of Revealing, but is also often carried by other gods directly associated with the Horus saga, including Set, Isis, Thoth and Anubis. In Crowley’s Thoth Tarot, the 5, 6 and 7 of Wands all depict the Phoenix Wand (with its two GD companions, the Lotus Wand and Orb Wand) and AC refers to it as such. In The Book of Thoth while commenting on the Magus card he writes that Thoth is sometimes depicted carrying a Phoenix Wand, “symbolising resurrection through the generative process. In his left hand is the Ankh, which represents a sandal-strap; that is to say, the means of progress through the worlds, which is the distinguishing mark of godhead.” And again in Across the Gulf Crowley writes, “By the bed stood the Priest of Horus with his heavy staff, the Phoenix for its head, the prong for its foot. Watchful he stood lest Sebek should rise from the abyss.”

In The Mass of the Phoenix blood is behaving in the magical capacity as the vital essence. It is acting in a magical capacity in its conjunction with the Host (the bread) which is feminine. The introduction of the vital essence into a physical medium for its transmutation and transmission is similar to the Bennu’s ashes being preserved in a host of resinous woods and gums. This recalls the blood (of the bird) being used to feed the host (baked from the ashes of the bird) in Chemical Marriage, the result being a living (yet soulless, and so unconscious) and royal host.

The blood in the Mass of the Phoenix is drawn from the Magician’s breast by a burin. This blood is the will or energy of a Magician. The burin, a weapon used for carving (talismans), is the magical weapon of Aries along with “the horns” and “energy.” Aries, in Hebrew, is הלט, Heleth, 44. The Horns adorned Exodus’ Altar of Incense. Aries, in the Tarot, is the Emperor, Sulphur. Again, Sulphur enters the picture as that which is being transmuted. He marks on this inner alchemy, “Use all thine energy to rule thy thought: burn up thy thought as the Phoenix.” While the Emperor, Atu IV, shows a red eagle, sulfur, the he blood itself is dem, that being daleth (the Empress, Salt) and Mem (the Hanged Man, Mercury).

The blood can also be Shamayim, which is Azoth. Herr von Welling gives an interesting interpretation of this mysterious substance,